Equity Evolution: CAN’s Growth Story

Vol. 3

October 12, 2021

October is National Disability Employment Awareness Month, and as we continue to reflect on CAN’s collective journey to becoming a more just and equitable organization, it’s important to explore the intersectionalities that make up one’s identity and realize that ‘identity’ isn’t a simple category. That starts with me: hello, my name is Nat Rosales. I am queer. I am nonbinary. I am Latinx. I am a graduate student. I am CAN’s student assistant, and this is my journey.

I have never felt like I have fit in – I have always felt like I am a background character sitting on the sidelines trying to grasp at any straw available to me to try to find a place for myself. I’ve grown up hyper-aware that I am not “normal,” and I spent the entirety of my formative years figuring out how to change myself in order to be palatable to the masses. No matter what I did, I still felt like I didn’t fit in and the simplest answer is because I see the world completely differently from others. Since receiving my autism diagnosis, I have felt like a giant weight had been taken off my shoulders because I was able to finally describe my lived experiences with a new set of terminology that made way too much sense, or at least to me it did.

I rejected my diagnosis for a long time, stemming from my lack of understanding. I had always considered myself a very open-minded and accepting individual, but why was it so hard for me to understand that I was different? Why was it so hard to be accepting of myself? With this diagnosis came the long journey of unlearning the internalized ableism that runs within myself and that runs rampant in our society. What is ableism? To quote Access Living: “Ableism is the discrimination of and social prejudice against people with disabilities based on the belief that typical abilities are superior.” It’s this notion that we need some type of “fixing,” or that families need to mourn the “loss of opportunity” that their child will have due to their diagnosis, which is seen in large organizations such as Autism Speaks.

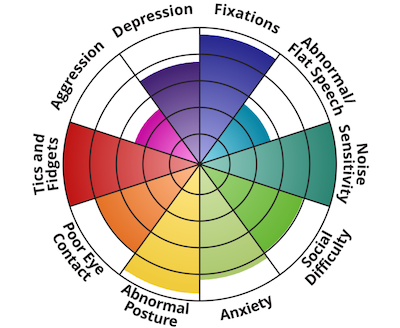

Ableism is so deeply ingrained in American society, that at times it seems like “disability” is a dirty word. It’s something that cannot be embraced or shared with others for the fear of being seen as lesser. This is seen when people fear that disclosing their disability in job applications will make them seem unfit for the role or as a liability. In interpersonal sectors, it’s seen when people don’t believe that someone has a disability because they “don’t look like it.” Disability doesn’t have a look and trying to fit disabled people into these boxes simply continues to perpetuate stereotypes and alienate individuals. When I disclose my diagnosis to people who I have known for years and years, the minute that they hear “I’m autistic,” they don’t believe me because “I don’t look like I’m autistic.” Autism doesn’t have a “look,” it is a spectrum that holds a wide variety of support needs that are unique to every individual.

The sensory issues that affect me everyday – adhering to specific rituals when it comes to food, finding extreme discomfort in loud and too-bright environments like grocery stores and malls, and not knowing how to interact with people without developing a script – are just some of the things that I experience as an autistic adult. But these challenges don’t hinder me from realizing that my inclination towards learning, my special interests in philosophy and interior design, and my incredibly overactive imagination that materializes itself in writing are also a consequence of my autism. I’ve learned to embrace every part of myself, and even if I have to do extra steps to keep myself grounded and comfortable, I wouldn’t change anything about how I see the world.

However, my experience and the way that I have learned to navigate the world is not how every disabled person exists. Unfortunately, a culture with inherent ableism affects every structure and system that makes up our culture. It is an entire culture that has systematically put an entire population at a disadvantage. This is something that affects disabled folks throughout the United States as a whole. This is seen when a large percentage of disabled folk are victims of the prison industrial complex, with individuals behind bars in state and federal prison being three times more likely to report having a disability compared to non-incarcerated people. This is also seen when children with disabilities experience traumatic stress growing up, with 64% of children that are being mistreated report having a disability. In educational settings, these children are more susceptible to being bullied, as being characterized as “problem children”, or the inverse and are simply stuck in the sidelines and aren’t given the adequate space and opportunity to truly grow and thrive as individuals.

How can this culture shift? How can we, as individuals, organizations, institutions, create lasting change that doesn’t see disabled individuals as an “other”, but as an equally valuable aspect of society? How have I learned to unlearn the ableism that I grew up seeing in my community and the media I was consuming?

It all begins with understanding – understanding that a disability doesn’t define the entirety of a person. It begins with confronting ableism in your closest circles, fostering a new perspective on the rights of disabled people. And it begins with listening. Listen to the disabled people in your lives, your coworkers, your friends and family, your acquaintances that you see randomly on the bus. Learn to unlearn these harmful practices in order to make the spaces you occupy more welcoming, accessible, and equitable. We can all work together to change the way we see disability and to make individuals unashamed for being who they are. Little steps help shift the culture – even if it feels like you aren’t doing much, doing as little as asking about what your organization is doing to become more accessible is enough to get that dialogue started.

My name is Nat. I am queer. I am nonbinary. I am Latinx. I am a graduate student. I am CAN’s student assistant. And I am autistic.

Resources for Unlearning Ableism:

- Unlearning Ableism via University of Illinois, Chicago

- Everyday Ableism: What it is and how to stop doing it via Medium

Resources for Being a Better Ally to Disabled Folks:

- 6 Ways to be a Better Friend to a Disabled Person via Forbes

- Disability Inclusion at Work: What it is and Why it matters via Understood.org

In Solidarity,

Nat Rosales (they/them)